Facebook is leaning on fears of China exporting its authoritarian social values to counter arguments that it should be broken up or slowed down. Its top executives have each claimed that if the U.S. limits its size, blocks its acquisitions, or bans its cryptocurrency, Chinese company’s absent these restrictions will win abroad, bringing more power and data to their government. CEO Mark Zuckerberg, COO Sheryl Sandberg, and VP of communications Nick Clegg have all expressed this position.

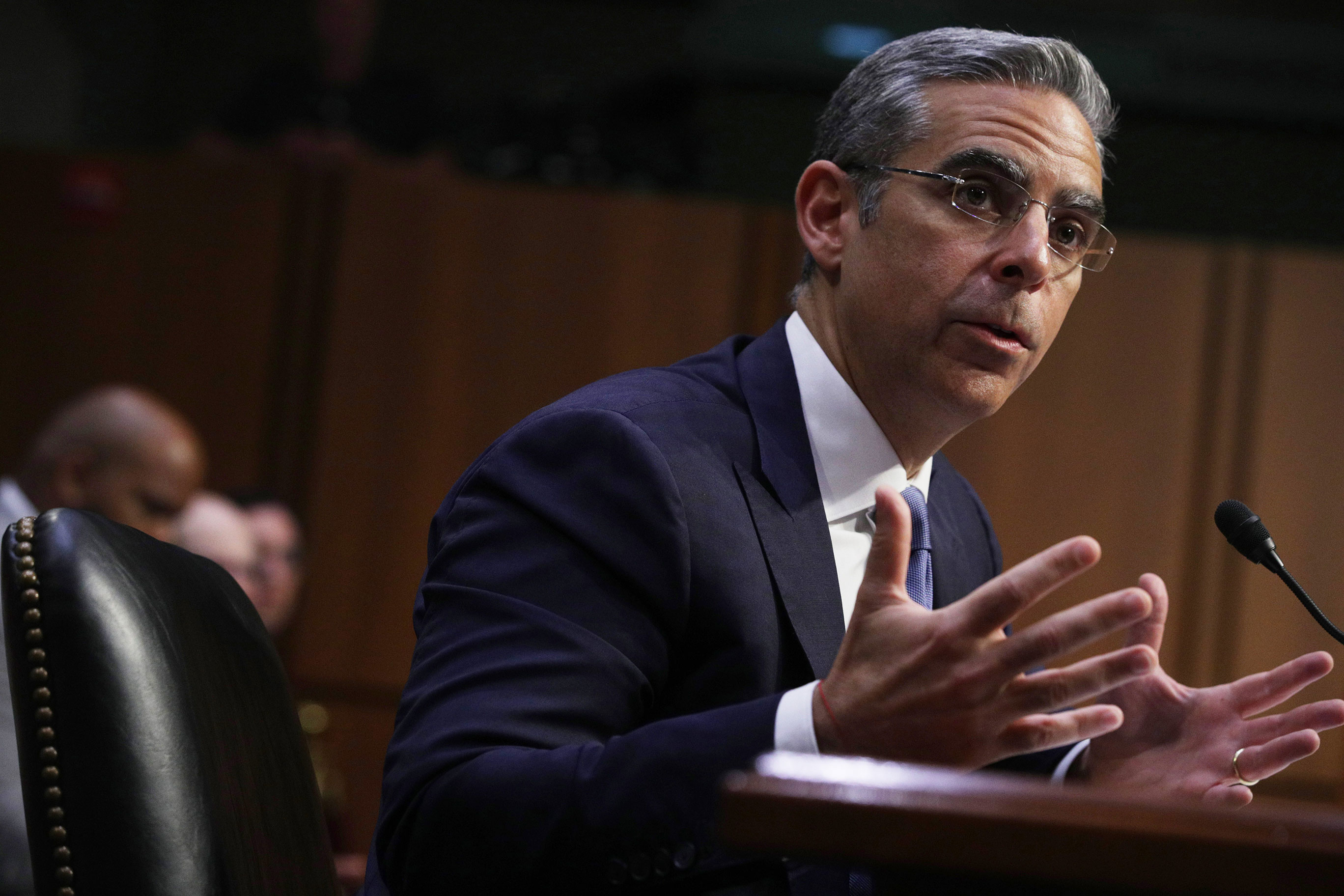

The latest incarnation of this talking point came in today and yesterday’s congressional hearings over Libra, the Facebook-spearheaded digital currency it hopes to launch in the first half of 2020. Facebook’s head of its blockchain subsidiary Calibra David Marcus wrote in his prepared remarks to the House Financial Services Committee today that:

“I believe that if America does not lead innovation in the digital currency and payments area, others will. If we fail to act, we could soon see a digital currency controlled by others whose values are dramatically different”

WASHINGTON, DC – JULY 16: Head of Facebook’s Calibra David Marcus testifies during a hearing before Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee July 16, 2019 on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC. The committee held the hearing on “Examining Facebook’s Proposed Digital Currency and Data Privacy Considerations.” (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Marcus also told the Senate Banking Subcommittee yesterday that “I believe if we stay put we’re going to be in a situation in 10, 15 years where half the world is on a blockchain technology that is out of reach of our national-security apparatus” .

This argument is designed to counter House-drafted “Keep Big Tech Out Of Finance” legislation that Reuters reports would declare that companies like Facebook that earn over $25 billion in annual revenue “may not establish, maintain, or operate a digital asset . . . that is intended to be widely used as medium of exchange, unit of account, store of value, or any other similar function.”

The message Facebook is trying to deliver is that cryptocurrencies are inevitable. Blocking Libra would just open the door to even less scrupulous actors controlling the technology. Facebook’s position here isn’t limited to cryptocurrencies, though.

The concept crystallized exactly a year ago when Zuckerberg said “I think you have this question from a policy perspective, which is, do we want American companies to be exporting across the world?” in an interview with Recode’s Kara Swisher.

“We grew up here, I think we share a lot of values that I think people hold very dear here, and I think it’s generally very good that we’re doing this, both for security reasons and from a values perspective. Because I think that the alternative, frankly, is going to be the Chinese companies. If we adopt a stance which is that, ‘Okay, we’re gonna, as a country, decide that we wanna clip the wings of these companies and make it so that it’s harder for them to operate in different places, where they have to be smaller,’ then there are plenty of other companies out that are willing and able to take the place of the work that we’re doing.”

When asked if he specifically meant Chinese companies, Zuckerberg doubled down, saying:

“Yeah. And they do not share the values that we have. I think you can bet that if the government hears word that it’s election interference or terrorism, I don’t think Chinese companies are going to wanna cooperate as much and try to aid the national interest there.”

WASHINGTON, DC – APRIL 10: Facebook co-founder, Chairman and CEO Mark Zuckerberg testifies before a combined Senate Judiciary and Commerce committee hearing in the Hart Senate Office Building on Capitol Hill April 10, 2018 in Washington, DC. Zuckerberg, 33, was called to testify after it was reported that 87 million Facebook users had their personal information harvested by Cambridge Analytica, a British political consulting firm linked to the Trump campaign. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

This April, Zuckerberg went deeper when he described how Facebook would refuse to comply with data localization laws in countries with poor track records on human rights. The CEO explained the risk of data being stored in other countries, which is precisely might happen if regulators hamper Facebook and innovation happens elsewhere. Zuckerberg told philosopher Yuval Harari that:

“When I look towards the future, one of the things that I just get very worried about is the values that I just laid out [for the internet and data] are not values that all countries share. And when you get into some of the more authoritarian countries and their data policies, they’re very different from the kind of regulatory frameworks that across Europe and across a lot of other places, people are talking about or put into place . . . And the most likely alternative to each country adopting something that encodes the freedoms and rights of something like GDPR, in my mind, is the authoritarian model, which is currently being spread, which says every company needs to store everyone’s data locally in data centers and then, if I’m a government, I can send my military there and get access to whatever data I want and take that for surveillance or military.

I just think that that’s a really bad future. And that’s not the direction, as someone who’s building one of these internet services, or just as a citizen of the world, I want to see the world going. If a government can get access to your data, then it can identify who you are and go lock you up and hurt you and your family and cause real physical harm in ways that are just really deep.”

Facebook’s newly hired head of communications Nick Clegg told reporters back in January that:

“These are of course legitimate questions, but we don’t hear so much about China, which combines astonishing ingenuity with the ability to process data on a vast scale without the legal and regulatory constraints on privacy and data protection that we require on both sides of the Atlantic . . . [and this data could be] put to more sinister surveillance ends, as we’ve seen with the Chinese government’s controversial social credit system.”

In response to Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes’ call that Facebook should be broken up, Clegg wrote in May that “Facebook shouldn’t be broken up — but it does need to be held to account. Anyone worried about the challenges we face in an online world should look at getting the rules of the internet right, not dismantling successful American companies.”

He hammered home the alternative the next month during a speech in Berlin:

“If we in Europe and America don’t turn off the white noise and begin to work together, we will sleepwalk into a new era where the internet is no longer a universal space but a series of silos where different countries set their own rules and authoritarian regimes soak up their citizens’ data while restricting their freedom . . . If the West doesn’t engage with this question quickly and emphatically, it may be that it isn’t ours to answer. The common rules created in our hemisphere can become the example the rest of the world follows.”

COO Sheryl Sandberg made the point most directly in an interview with CNBC in May:

“You could break us up, you could break other tech companies up, but you actually don’t address the underlying issues people are concerned about . . . While people are concerned with the size and power of tech companies, there’s also a concern in the United States about the size and power of Chinese tech companies and the … realization that those companies are not going to be broken up.”

WASHINGTON, DC – SEPTEMBER 5: Facebook chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg testifies during a Senate Intelligence Committee hearing concerning foreign influence operations’ use of social media platforms, on Capitol Hill, September 5, 2018 in Washington, DC. Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey and Facebook chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg faced questions about how foreign operatives use their platforms in attempts to influence and manipulate public opinion. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Scared Tactics

Indeed, China does not share the United States’ values on individual freedoms and privacy. And yes, breaking up Facebook could weaken its products like WhatsApp, providing more opportunities for apps like Chinese tech giant Tencent’s WeChat to proliferate.

But letting Facebook off the hook won’t solve the problems China’s influence poses to an open and just internet. If Framing the issue as ‘strong regulation lets China win’ creates a false dichotomy. There are more constructive approaches if Zuckerberg seriously wants to work with the government on exporting freedom via the web. And the distrust Facebook has accrued through the mistakes it’s made in the absence of proper regulation arguably do plenty to hurt the perception of how American ideals are spread through its tech companies.

Breaking up Facebook may not be the answer, especially if it’s done in retaliation for its wrong-doings instead of as a coherent way to prevent more in the future. To that end, a better approach might be stopping future acquisitions of large or rapidly growing social networks, forcing it to offer true data portability so existing users have the freedom to switch to competitors, applying proper oversight of its privacy policies, and requiring a slow rollout of Libra with testing in each phase to ensure it doesn’t screw consumers, enable terrorists, or jeopardize the world economy.

Resorting to scare tactics shows that it’s Facebook that’s scared. Years of growth over safety strategy might finally catch up with it. The $5 billion FTC fine is a slap on the wrist for a company that profits more than that per quarter, but a break-up would do real damage. Instead of fear-mongering, Facebook would be better served by working with regulators in good faith while focusing more on preempting abuse. Perhaps it’s politically savvy to invoke the threat of China to stoke the worries of government officials, and it might even be effective. That doesn’t make it right.

Read Full Article