Choice for consumers compels fair treatment by corporations. When people can easily move to a competitor, it creates a natural market dynamic coercing a business to act right. When we can’t, other regulations just leave us trapped with a pig in a fresh coat of lipstick.

That’s why as the FTC considers how many billions to fine Facebook or which executives to stick with personal liability or whether to go full-tilt and break up the company, I implore it to consider the root of how Facebook gets away with abusing user privacy: there’s no simple way to switch to an alternative.

If Facebook users are fed up with the surveillance, security breaches, false news, or hatred, there’s no western general purpose social network with scale for them to join. Twitter is for short-form public content, Snapchat is for ephemeral communication. Tumblr is neglected. Google+ is dead. Instagram is owned by Facebook. And the rest are either Chinese, single-purpose, or tiny.

If Facebook users are fed up with the surveillance, security breaches, false news, or hatred, there’s no western general purpose social network with scale for them to join. Twitter is for short-form public content, Snapchat is for ephemeral communication. Tumblr is neglected. Google+ is dead. Instagram is owned by Facebook. And the rest are either Chinese, single-purpose, or tiny.

No, I don’t expect the FTC to launch its own “Fedbook” social network. But what it can do is pave an escape route from Facebook so worthy alternatives become viable options. That’s why the FTC must require Facebook offer truly interoperable data portability for the social graph.

In other words, the government should pass regulations forcing Facebook to let you export your friend list to other social networks in a privacy-safe way. This would allow you to connect with or follow those people elsewhere so you could leave Facebook without losing touch with your friends. The increased threat of people ditching Facebook for competitors would create a much stronger incentive to protect users and society.

The slate of potential regulations for Facebook currently being discussed by the FTC’s heads include a $3 billion to $5 billion fine or greater, holding Facebook CEO personally liable for violations of an FTC consent decree, creating new privacy and compliance positions including one held by executive that could be filled by Zuckerberg, creating an independent oversight committee to review privacy and product decisions, accordng to the New York Times and Washington Post. More extreme measures like restricting how Facebook collects and uses data for ad targeting, blocking future acquisitions, or breaking up the company are still possible but seemingly less likely.

Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes (right) recently wrote a scathing call to break up Facebook.

Breaking apart Facebook is a tantalizing punishment for the company’s wrongdoings. Still, I somewhat agree with Zuckerberg’s response to co-founder Chris Hughes’ call to split up the company, which he said “isn’t going to do anything to help” directly fix Facebook’s privacy or misinformation issues. Given Facebook likely wouldn’t try to make more acquisitions of big social networks under all this scrutiny, it’d benefit from voluntarily pledging not to attempt these buys for at least three to five years. Otherwise, regulators could impose that ban, which might be more politically attainable with fewer messy downstream effects,

Yet without this data portability regulation, Facebook can pay a fine and go back to business as usual. It can accept additional privacy oversight without fundamentally changing its product. It can become liable for upholding the bare minimum letter of the law while still breaking the spirit. And even if it was broken up, users still couldn’t switch from Facebook to Instagram, or from Instagram and WhatsApp to somewhere new.

Facebook Kills Competition With User Lock-In

When faced with competition in the past, Facebook has snapped into action improving itself. Fearing Google+ in 2011, Zuckerberg vowed “Carthage must be destroyed” and the company scrambled to launch Messenger, the Timeline profile, Graph Search, photo improvements and more. After realizing the importance of mobile in 2012, Facebook redesigned its app, reorganized its teams, and demanded employees carry Android phones for “dogfooding” testing. And when Snapchat was still rapidly growing into a rival, Facebook cloned its Stories and is now adopting the philosophy of ephemerality.

Mark Zuckerberg visualizes his social graph at a Facebook conference

Each time Facebook felt threatened, it was spurred to improve its product for consumers. But once it had defeated its competitors, muted their growth, or confined them to a niche purpose, Facebook’s privacy policies worsened. Anti-trust scholar Dina Srinivasan explains this in her summary of her paper “The Anti-Trust Case Against Facebook”:

“When dozens of companies competed in an attempt to win market share, and all competing products were priced at zero—privacy quickly emerged as a key differentiator. When Facebook entered the market it specifically promised users: “We do not and will not use cookies to collect private information from any user.” Competition didn’t only restrain Facebook’s ability to track users. It restrained every social network from trying to engage in this behavior . . . the exit of competition greenlit a change in conduct by the sole surviving firm. By early 2014, dozens of rivals that initially competed with Facebook had effectively exited the market. In June of 2014, rival Google announced it would shut down its competitive social network, ceding the social network market to Facebook.

For Facebook, the network effects of more than a billion users on a closed-communications protocol further locked in the market in its favor. These circumstances—the exit of competition and the lock-in of consumers—finally allowed Facebook to get consumers to agree to something they had resisted from the beginning. Almost simultaneous with Google’s exit, Facebook announced (also in June of 2014) that it would begin to track users’ behavior on websites and apps across the Internet and use the data gleaned from such surveillance to target and influence consumers. Shortly thereafter, it started tracking non-users too. It uses the “like” buttons and other software licenses to do so.”

This is why the FTC must seek regulation that not only punishes Facebook for wrongdoings, but that lets consumers do the same. Users can punch holes in Facebook by leaving, both depriving it of ad revenue and reducing its network effect for others. Empowering them with the ability to take their friend list with them gives users a taller seat at the table. I’m calling for what University Of Chicago professors Luigi Zingales and Guy Rolnik termed a Social Data Portability Act.

Luckily, Facebook already has a framework for this data portability through a feature called Find Friends. You connect your Facebook account to another app, and you can find your Facebook friends who are already on that app.

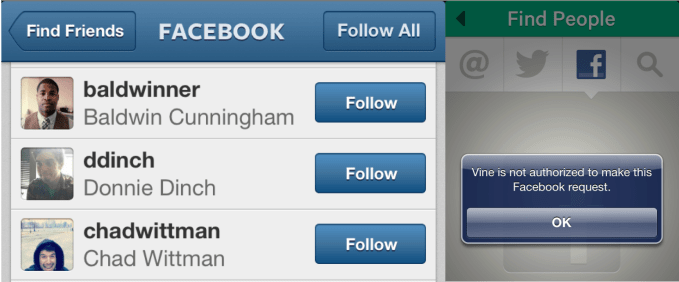

But the problem is that in the past, Facebook has repeatedly blocked competitors from using Find Friends. That includes cutting off Twitter, Vine, Voxer, and MessageMe, while Phhhoto was blocked from letting you find your Instagram friends…six months before Instagram copied Phhhoto’s core back-and-forth GIF feature and named it Boomerang. Then there’s the issue that you need an active Facebook account to use Find Friends. That nullifies its utility as a way to bring your social graph with you when you leave Facebook.

Facebook’s “Find Friends” feature used to let Twitter users follow their Facebook friends, but Facebook later cut off access for competitors including Twitter and Vine seen here

The social network does offer a way to “Download Your Information” which is helpful for exporting photos, status updates, messages, and other data about you. Yet the friend list can only be exported as a text list of names in HTML or JSON format. Names aren’t linked to their corresponding Facebook profiles or any unique identifier, so there’s no way to find your friend John Smith amongst everyone with that name on another app. And less than 5 percent of my 2800 connections had used the little-known option to allow friends to export their email address. What about the big “Data Transfer Project” Facebook announced 10 months ago in partnership with Google, Twitter, and Microsoft to provide more portability? It’s released nothing so far, raising questions of whether it was vaporware designed to ward off regulators.

Essentially, this all means that Facebook provides zero portability for your friendships. That’s what regulators need to change. There’s already precedent for this. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 saw FCC require phone service carriers to allow customers to easily port their numbers to another carrier rather than having to be assigned a new number. If you think of a phone number as a method by which friends connect with you, it would be reasonable for regulators to declare that the modern equivalent — your social network friend connections — must be similarly portable.

How To Unchain Our Friendships

Facebook should be required to let you export a truly interoperable friend list that can be imported into other apps in a privacy-safe way.

To do that, Facebook should allow you to download a version of the list that feature hashed versions of the phone numbers and email addresses friends used to sign up. You wouldn’t be able to read that contact info or freely import and spam people. But Facebook could be required to share documentation teaching developers of other apps to build a feature that safely cross-checks the hashed numbers and email addresses against those of people who had signed up for their app. That developer wouldn’t be able to read the contact info from Facebook either, or store any useful data about people who hadn’t signed up for their app. But if the phone number or email address of someone in your exported Facebook friend list matched one of their users, they could offer to let you connect with or follow them.

To do that, Facebook should allow you to download a version of the list that feature hashed versions of the phone numbers and email addresses friends used to sign up. You wouldn’t be able to read that contact info or freely import and spam people. But Facebook could be required to share documentation teaching developers of other apps to build a feature that safely cross-checks the hashed numbers and email addresses against those of people who had signed up for their app. That developer wouldn’t be able to read the contact info from Facebook either, or store any useful data about people who hadn’t signed up for their app. But if the phone number or email address of someone in your exported Facebook friend list matched one of their users, they could offer to let you connect with or follow them.

This system would let you save your social graph, delete your Facebook account, and then find your friends on other apps without ever jeopardizing the privacy of their contact info. Users would no longer be locked into Facebook and could freely choose to move their friendships to whatever social network treats them best. And Facebook wouldn’t be able to block competitors from using it.

The result would much more closely align the goals of users, Facebook, and the regulators. Facebook wouldn’t merely be responsible to the government for technically complying with new fines, oversight, or liability. It would finally have to compete to provide the best social app rather than relying on its network effect to handcuff users to its service.

This same model of data portability regulation could be expanded to any app with over 1 billion users, or even 100 million users to ensure YouTube, Twitter, Snapchat, or Reddit couldn’t lock down users either. By only applying the rule to apps with a sufficiently large user base, the regulation wouldn’t hinder new startup entrants to the market and accidentally create a moat around well-funded incumbents like Facebook that can afford the engineering chore. Data portability regulation combined with a fine, liability, oversight, and a ban on future acquisitions of social networks could set Facebook straight without breaking it up.

Users have a lot of complaints about Facebook that go beyond strictly privacy. But their recourse is always limited because for many functions there’s nowhere else to go, and it’s too hard to go there. By fixing the latter, the FTC could stimulate the rise of Facebook alternatives so that users rather regulators can play king-maker.

Read Full Article