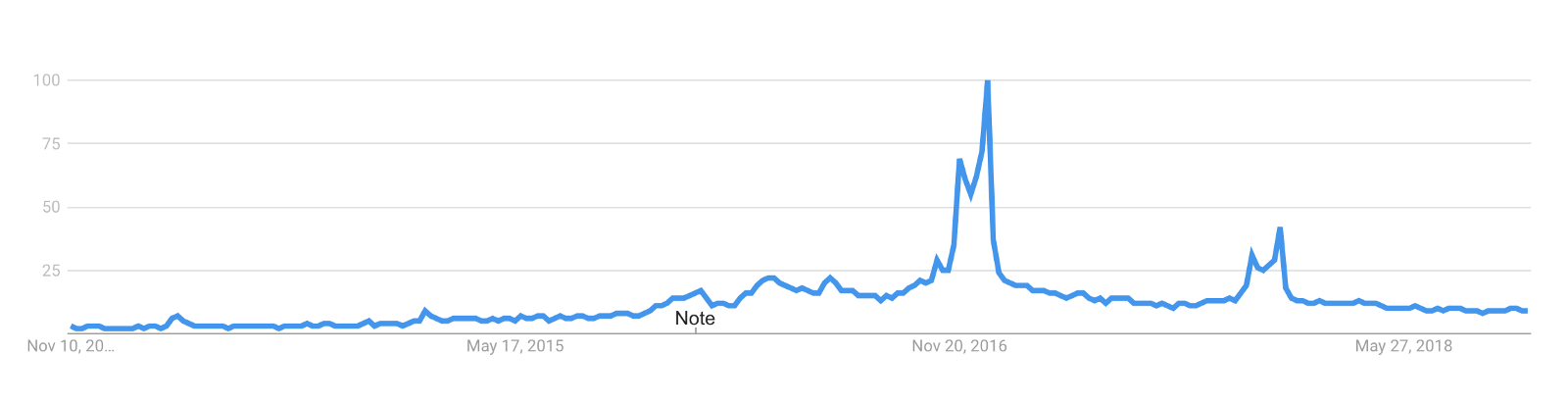

Virtual Reality is in a public relations slump. Two years ago the public’s expectations for virtual reality’s potential was at its peak. Many believed (and still continue to believe) that VR would transform the way we connect, interact, and communicate in our personal and professional lives.

Google Trends highlighting search trends related to Virtual Reality over time; the “note” refers to an improvement in Google’s data collection system that occurred in early 2016

It’s easy to understand why this excitement exists once you put on a head mounted display. While there are still a limited number of compelling experiences, after you test some of the early successes in the field, it’s hard not to extrapolate beyond the current state of affairs to a magnificent future where the utility of virtual reality technology is pervasive.

However, many problems still exist. The all-in cost for state of the art headsets is still out of reach for the mass market. Most ‘high-quality’ virtual reality experiences still require users to be tethered to their desktops. The setup experience for mass market users is lathered in friction. When it comes down to it, the holistic VR experience is a non-starter for most people. We are effectively in what Gartner refers to as the “trough of disillusionment.”

Gartner’s hype cycle for “Human-Machine Interface” in 2018 places many related VR related fields (e.g., Mixed Reality, AR, HMDs, etc.) in the “Trough of Disillusionment”

Yet, the virtual reality market has continued its slow march to mass adoption, and there are tangible indicators that suggest we could be nearing an inflection point.

A shift towards sustainable hardware growth

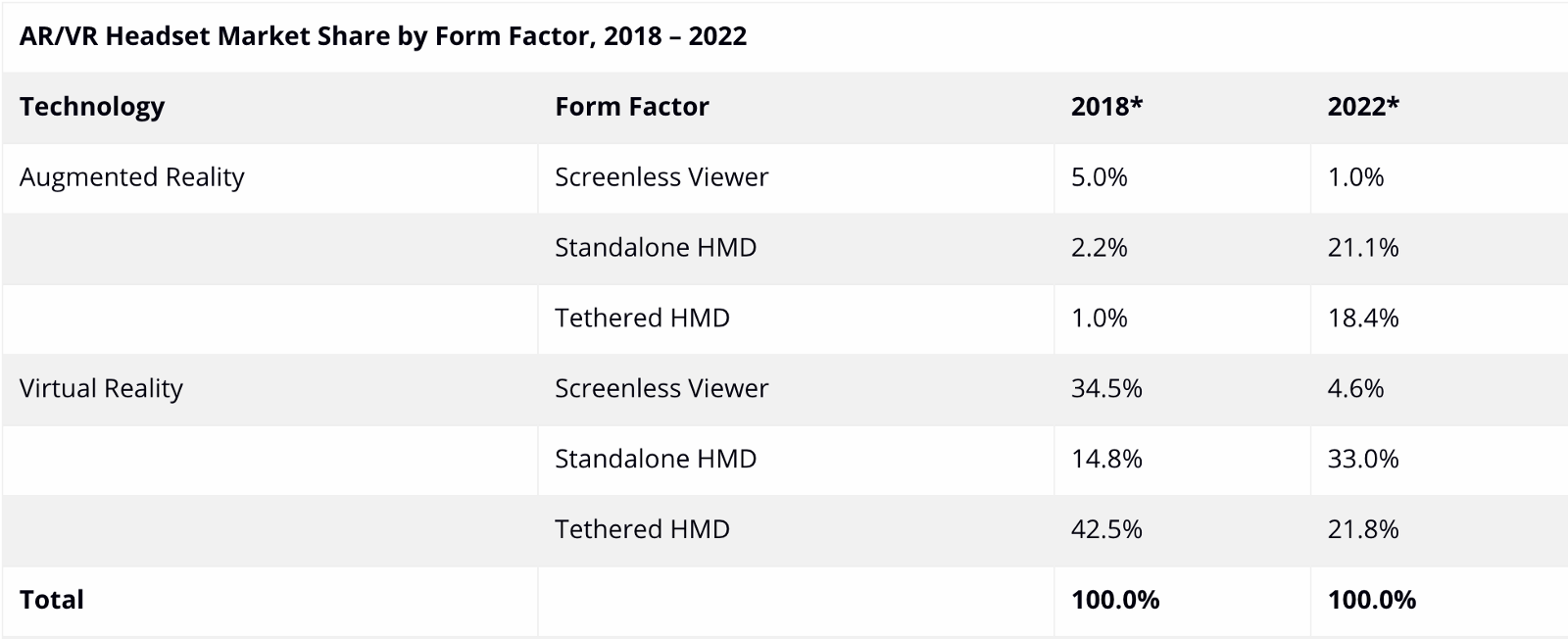

What you do and do not consider a virtual reality display can dramatically impact your view on the state of the VR hardware industry. Head-mounted displays (HMDs) can be categorized in three different ways:

- Screenless viewers — affordable devices that turn smartphones into a VR experience (e.g., Google Glass, Samsung Gear VR, etc.)

- Standalone HMDs — devices that are not connected to a computer and can independently run content (e.g., Oculus Go, Lenovo Mirage Solo, etc.)

- Tethered HMDs — devices that are connected to a desktop computer in order to run content (e.g., HTC Vive, Oculus Pro, etc.)

2018 has seen disappointing progress in aggregate headset growth. The overall market is forecasted to ship 8.9M headsets in 2018, up from an approximate aggregate shipment of ~8.3M in 2017, according to IDC. On the surface, those numbers hardly describe a market at its inflection point.

However, most of the decline in growth rate can be attributed to two factors. First, screenless viewers have seen a significant decline in shipments as device manufacturers have stopped shipping them alongside smartphones. In the second quarter of 2018, 409K screenless viewers were shipped compared to approximately 1M in the second quarter of 2017. Second, tethered VR headsets have also declined as manufacturers have slowed down the pricing discounts that acted as a steroid to sales growth in 2017.

Looking at the market for standalone HMDs, however, reveals a more promising figure. Standalone VR headsets grew 417% due to the global availability of the Oculus Go and Xiaomi Mi VR. Over time, these headsets are going to be the driver of the VR market as they offer significant advantages compared to tethered headsets.

The shift from tethered to standalone VR headsets is significant. It represents a paradigm shift within the immersive ecosystem, where developers have a truly mobile platform that is powerful enough to enable compelling user experiences.

IDC forecasts for AR/VR headset market share by form factor, 2018–2022

A premium market segment

There are a few names that come to mind when thinking about products that are available for purchase in the VR market: Samsung, Facebook (Oculus), HTC, and Playstation. A plethora of new products from these marquee names — and products from new companies entering the market — are opening the category for a new customer segment.

For the past few years, the market effectively had two segments. The first was a “mass market” segment with notorious devices such as the Google Cardboard and the Samsung Gear, which typically sold for under $100 and offered severely constrained experiences to consumers. The second segment was a “pro market” with a few notable devices, such as the HTC Vive, that required absurdly powerful computing rigs to operate, but offered consumers more compelling, immersive experiences.

It’s possible that this new emerging segment will dramatically open up the total addressable VR market. This “premium” market segment offers product alternatives that are somewhat more expensive than the mass market, but are significantly differentiated in the potential experiences that can be offered (and with much less friction than the “pro market”).

The Oculus Go, the Xiaomi Mi VR, and the Lenovo Solo are the most notable products in this segment. They are the fastest growing devices in this segment, and represent a new wave of products that will continue to roll out. This segment could be the tipping point for when we move from the early adopters to the early majority in the VR product adoption curve.

A number of other products have also been released throughout 2018 that fall into this category, such as Lenovo’s Mirage Solo and Xiaomi’s Mi VR. Even more so, Oculus recently announced that they’ll be shipping a new headset called Quest this spring, which will sell for $399 and will be the most powerful example of a premium device to date. The all-in price range of ~$200–400 places these devices in a segment consumers are already conditioned to pay (think iPad’s, gaming consoles, etc.), and they offer differentiated experiences primarily attributed to the fact that they are standalone devices.

Read Full Article