The German Federal Cartel Office’s decision to order Facebook to change how it processes users’ personal data this week is a sign the antitrust tide could at last be turning against platform power.

One European Commission source we spoke to, who was commenting in a personal capacity, described it as “clearly pioneering” and “a big deal”, even without Facebook being fined a dime.

The FCO’s decision instead bans the social network from linking user data across different platforms it owns, unless it gains people’s consent (nor can it make use of its services contingent on such consent). Facebook is also prohibited from gathering and linking data on users from third party websites, such as via its tracking pixels and social plugins.

The order is not yet in force, and Facebook is appealing, but should it come into force the social network faces being de facto shrunk by having its platforms siloed at the data level.

To comply with the order Facebook would have to ask users to freely consent to being data-mined — which the company does not do at present.

Yes, Facebook could still manipulate the outcome it wants from users but doing so would open it to further challenge under EU data protection law, as its current approach to consent is already being challenged.

The EU’s updated privacy framework, GDPR, requires consent to be specific, informed and freely given. That standard supports challenges to Facebook’s (still fixed) entry ‘price’ to its social services. To play you still have to agree to hand over your personal data so it can sell your attention to advertisers. But legal experts contend that’s neither privacy by design nor default.

The only ‘alternative’ Facebook offers is to tell users they can delete their account. Not that doing so would stop the company from tracking you around the rest of the mainstream web anyway. Facebook’s tracking infrastructure is also embedded across the wider Internet so it profiles non-users too.

EU data protection regulators are still investigating a very large number of consent-related GDPR complaints.

But the German FCO, which said it liaised with privacy authorities during its investigation of Facebook’s data-gathering, has dubbed this type of behavior “exploitative abuse”, having also deemed the social service to hold a monopoly position in the German market.

So there are now two lines of legal attack — antitrust and privacy law — threatening Facebook (and indeed other adtech companies’) surveillance-based business model across Europe.

A year ago the German antitrust authority also announced a probe of the online advertising sector, responding to concerns about a lack of transparency in the market. Its work here is by no means done.

Data limits

The lack of a big flashy fine attached to the German FCO’s order against Facebook makes this week’s story less of a major headline than recent European Commission antitrust fines handed to Google — such as the record-breaking $5BN penalty issued last summer for anticompetitive behaviour linked to the Android mobile platform.

But the decision is arguably just as, if not more, significant, because of the structural remedies being ordered upon Facebook. These remedies have been likened to an internal break-up of the company — with enforced internal separation of its multiple platform products at the data level.

This of course runs counter to (ad) platform giants’ preferred trajectory, which has long been to tear modesty walls down; pool user data from multiple internal (and indeed external sources), in defiance of the notion of informed consent; and mine all that personal (and sensitive) stuff to build identity-linked profiles to train algorithms that predict (and, some contend, manipulate) individual behavior.

Because if you can predict what a person is going to do you can choose which advert to serve to increase the chance they’ll click. (Or as Mark Zuckerberg puts it: ‘Senator, we run ads.’)

This means that a regulatory intervention that interferes with an ad tech giant’s ability to pool and process personal data starts to look really interesting. Because a Facebook that can’t join data dots across its sprawling social empire — or indeed across the mainstream web — wouldn’t be such a massive giant in terms of data insights. And nor, therefore, surveillance oversight.

Each of its platforms would be forced to be a more discrete (and, well, discreet) kind of business.

Competing against data-siloed platforms with a common owner — instead of a single interlinked mega-surveillance-network — also starts to sound almost possible. It suggests a playing field that’s reset, if not entirely levelled.

(Whereas, in the case of Android, the European Commission did not order any specific remedies — allowing Google to come up with ‘fixes’ itself; and so to shape the most self-serving ‘fix’ it can think of.)

Meanwhile, just look at where Facebook is now aiming to get to: A technical unification of the backend of its different social products.

Such a merger would collapse even more walls and fully enmesh platforms that started life as entirely separate products before were folded into Facebook’s empire (also, let’s not forget, via surveillance-informed acquisitions).

Facebook’s plan to unify its products on a single backend platform looks very much like an attempt to throw up technical barriers to antitrust hammers. It’s at least harder to imagine breaking up a company if its multiple, separate products are merged onto one unified backend which functions to cross and combine data streams.

Set against Facebook’s sudden desire to technically unify its full-flush of dominant social networks (Facebook Messenger; Instagram; WhatsApp) is a rising drum-beat of calls for competition-based scrutiny of tech giants.

This has been building for years, as the market power — and even democracy-denting potential — of surveillance capitalism’s data giants has telescoped into view.

Calls to break up tech giants no longer carry a suggestive punch. Regulators are routinely asked whether it’s time. As the European Commission’s competition chief, Margrethe Vestager, was when she handed down Google’s latest massive antitrust fine last summer.

Her response then was that she wasn’t sure breaking Google up is the right answer — preferring to try remedies that might allow competitors to have a go, while also emphasizing the importance of legislating to ensure “transparency and fairness in the business to platform relationship”.

But it’s interesting that the idea of breaking up tech giants now plays so well as political theatre, suggesting that wildly successful consumer technology companies — which have long dined out on shiny convenience-based marketing claims, made ever so saccharine sweet via the lure of ‘free’ services — have lost a big chunk of their populist pull, dogged as they have been by so many scandals.

From terrorist content and hate speech, to election interference, child exploitation, bullying, abuse. There’s also the matter of how they arrange their tax affairs.

The public perception of tech giants has matured as the ‘costs’ of their ‘free’ services have scaled into view. The upstarts have also become the establishment. People see not a new generation of ‘cuddly capitalists’ but another bunch of multinationals; highly polished but remote money-making machines that take rather more than they give back to the societies they feed off.

Google’s trick of naming each Android iteration after a different sweet treat makes for an interesting parallel to the (also now shifting) public perceptions around sugar, following closer attention to health concerns. What does its sickly sweetness mask? And after the sugar tax, we now have politicians calling for a social media levy.

Just this week the deputy leader of the main opposition party in the UK called for setting up a standalone Internet regulatory with the power to break up tech monopolies.

Talking about breaking up well-oiled, wealth-concentration machines is being seen as a populist vote winner. And companies that political leaders used to flatter and seek out for PR opportunities find themselves treated as political punchbags; Called to attend awkward grilling by hard-grafting committees, or taken to vicious task verbally at the highest profile public podia. (Though some non-democratic heads of state are still keen to press tech giant flesh.)

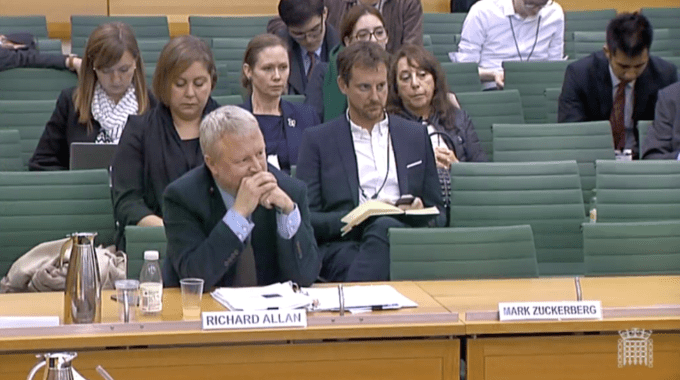

In Europe, Facebook’s repeat snubs of the UK parliament’s requests last year for Zuckerberg to face policymakers’ questions certainly did not go unnoticed.

Zuckerberg’s empty chair at the DCMS committee has become both a symbol of the company’s failure to accept wider societal responsibility for its products, and an indication of market failure; the CEO so powerful he doesn’t feel answerable to anyone; neither his most vulnerable users nor their elected representatives. Hence UK politicians on both sides of the aisle making political capital by talking about cutting tech giants down to size.

The political fallout from the Cambridge Analytica scandal looks far from done.

Quite how a UK regulator could successfully swing a regulatory hammer to break up a global Internet giant such as Facebook which is headquartered in the U.S. is another matter. But policymakers have already crossed the rubicon of public opinion and are relishing talking up having a go.

That represents a sea-change vs the neoliberal consensus that allowed competition regulators to sit on their hands for more than a decade as technology upstarts quietly hoovered up people’s data and bagged rivals, and basically went about transforming themselves from highly scalable startups into market-distorting giants with Internet-scale data-nets to snag users and buy or block competing ideas.

The political spirit looks willing to go there, and now the mechanism for breaking platforms’ distorting hold on markets may also be shaping up.

The traditional antitrust remedy of breaking a company along its business lines still looks unwieldy when faced with the blistering pace of digital technology. The problem is delivering such a fix fast enough that the business hasn’t already reconfigured to route around the reset.

Commission antitrust decisions on the tech beat have stepped up impressively in pace on Vestager’s watch. Yet it still feels like watching paper pushers wading through treacle to try and catch a sprinter. (And Europe hasn’t gone so far as trying to impose a platform break up.)

But the German FCO decision against Facebook hints at an alternative way forward for regulating the dominance of digital monopolies: Structural remedies that focus on controlling access to data which can be relatively swiftly configured and applied.

Vestager, whose term as EC competition chief may be coming to its end this year (even if other Commission roles remain in potential and tantalizing contention), has championed this idea herself.

In an interview on BBC Radio 4’s Today program in December she poured cold water on the stock question about breaking tech giants up — saying instead the Commission could look at how larger firms got access to data and resources as a means of limiting their power. Which is exactly what the German FCO has done in its order to Facebook.

At the same time, Europe’s updated data protection framework has gained the most attention for the size of the financial penalties that can be issued for major compliance breaches. But the regulation also gives data watchdogs the power to limit or ban processing. And that power could similarly be used to reshape a rights-eroding business model or snuff out such business entirely.

The merging of privacy and antitrust concerns is really just a reflection of the complexity of the challenge regulators now face trying to rein in digital monopolies. But they’re tooling up to meet that challenge.

Speaking in an interview with TechCrunch last fall, Europe’s data protection supervisor, Giovanni Buttarelli, told us the bloc’s privacy regulators are moving towards more joint working with antitrust agencies to respond to platform power. “Europe would like to speak with one voice, not only within data protection but by approaching this issue of digital dividend, monopolies in a better way — not per sectors,” he said. “But first joint enforcement and better co-operation is key.”

The German FCO’s decision represents tangible evidence of the kind of regulatory co-operation that could — finally — crack down on tech giants.

Blogging in support of the decision this week, Buttarelli asserted: “It is not necessary for competition authorities to enforce other areas of law; rather they need simply to identity where the most powerful undertakings are setting a bad example and damaging the interests of consumers. Data protection authorities are able to assist in this assessment.”

He also had a prediction of his own for surveillance technologists, warning: “This case is the tip of the iceberg — all companies in the digital information ecosystem that rely on tracking, profiling and targeting should be on notice.”

So perhaps, at long last, the regulators have figured out how to move fast and break things.

Read Full Article