Imagine you get a monthly paycheck on the 15th of the month but your bills come in on the 1st of the month. Between the 15th and 1st you must set a portion of your check aside to pay bills. This becomes a complicated budgeting equation. How much can I spend today vs how much do I need to set aside?

In a perfectly rational world people would reduce their consumption by the amount needed to afford their bills and have money left over to make it to the next payday. Sadly, this isn’t what happens. When income and bills are farther apart, we struggle to make the math work.

Researchers Brian Baugh and Jialan Wang found that financial shortfalls – payday loans and bank overdrafts – happen 18% more when there is a greater mismatch between the timing of someone’s income and the bills they owe.

We come up short.

Baugh offers some reasoning: When we get paid, we spend money. More money than usual. Research from Arna Olafsson and Michaela Pagel supports this. They find that both poor and rich households respond to the receipt of income, with the poorest households spending 70 percent more when they get paid than they would on an average day and the richest households spending 40 percent more. This inclination to spend more on payday makes the monthly budget harder to balance – and sometimes makes it unable to balance at all.

Many fintech companies are starting to address pay period timing, in hopes they can close the gap between income and consumption needs. Apps like Even, Earnin and PayActive provide people with instant access to their paycheck. Gig economy employers like Uber and Lyft have features that allow drivers to cash out immediately after they drive. For people who would otherwise get paid on a monthly schedule, this is critical. Jesse Shapiro of Harvard found that food stamp recipients consume 10 to 15 percent fewer calories the week before food stamps are disbursed. Even a few days matter. In Baugh’s study, the difference between a paycheck period of 35 days vs a paycheck period of 28 days resulted in 9% more instances of financial distress.

The question we should be asking now is what is the optimal timing for pay periods? Too long between checks causes hardship, but how short should pay periods become? These fintech companies are offering to “Make Any Day Payday” with promises that people can “Get your paycheck anytime you want.” While this smooths the gap between pay periods, given Olassof’s research, it may also serve to increase spending if everyday is payday.

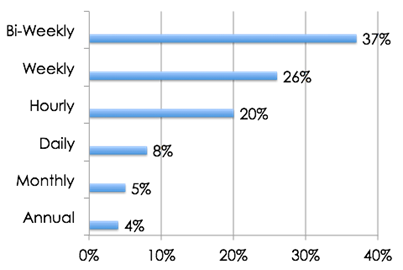

To dive deeper into this problem, our team sought to understand what employees preferred. As a reminder, our preferences don’t always represent what’s best for us. You may want to eat that chocolate cake, but that doesn’t mean it will help you with your summer dieting goals. However, we were curious: do people have the intuition that more frequent pay periods are better, and how frequent is optimal? To do this we asked 384 people making less than median income ($30,000 a year) to tell us their preferred pay schedule. Using Google Consumer Surveys, we gave them six payment schedules to choose from: Annual, Monthly, Bi-weekly, Weekly, Daily or Hourly.

What should people say? If everyone acts rationally, we would expect people to say they want to get paid hourly – immediately after working. It’s their money and they would be best off with unfettered access to it.

This is not what we found. Instead, people prefer to get paid on a bi-weekly or weekly schedule. Aggregating everyone’s responses, people preferred bi-weekly (37.2%), followed by weekly (26.6%).

Why aren’t more people choosing hourly or daily? While we can’t be sure, one guess is that Baugh’s findings ring true. Weekly and biweekly paychecks can act as a self control device for spending. If paydays were every day, they may be more tempted to spend on non-critical items, leaving less money for bills. Weekly and biweekly paychecks also serve as a way to fix the misalignment of income and bills that Baugh cites drives overdrafts and payday loans. Our team interviewed 40 people in Fresno, California and found this to be a popular budgeting strategy – one paycheck is used for the family car payment and one is used for rent.

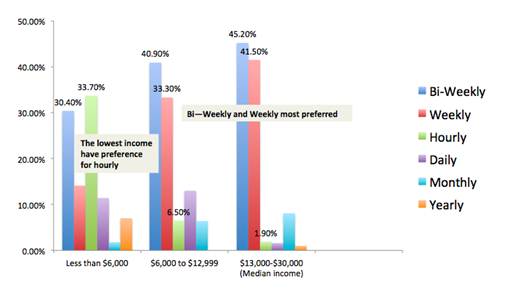

When we break out responses by income, we find some correlational differences across income groups. People reporting less than $6,000 income (50% below poverty line) are more likely to opt for an immediate pay schedule. As people’s income level rises above poverty (or part time status), the preference for weekly and bi-weekly pay schedules increases.

We also asked people to tell us how they would describe their personal need for money when paying their bills over the past year. No surprise, but the more people felt they needed money for immediate bills (or feeling scarce) the higher the demand for more frequent paychecks (hourly or weekly).

The verdict?

More research is needed to determine the effects of the growing trend to offer instant access to your paycheck. These apps can bridge critical gaps for people living paycheck to paycheck, but they may also have some detrimental effects if Baugh and Olafsson’s findings hold. If apps help people make everyday payday, and each payday results in higher spending, the end of the month may be much harder to get to.

Key insights for companies trying to improve people’s financial lives

- Help move people off a monthly pay cycle. Our study suggests that lower income individuals don’t prefer monthly and other research suggests it has costly implications for their financial lives.

- Help people match up their income and their bills. Lenders can do this upon loan origination or fintech apps (like EarnUp) can help people automate timing.

- Provide (thoughtful) access to the paycheck. Apps could ask people up front to precommit to when they want to take money from their paycheck. This would still allow people to have access, but could possibly slow down an urge to withdraw too frequently.

Read Full Article

No comments:

Post a Comment