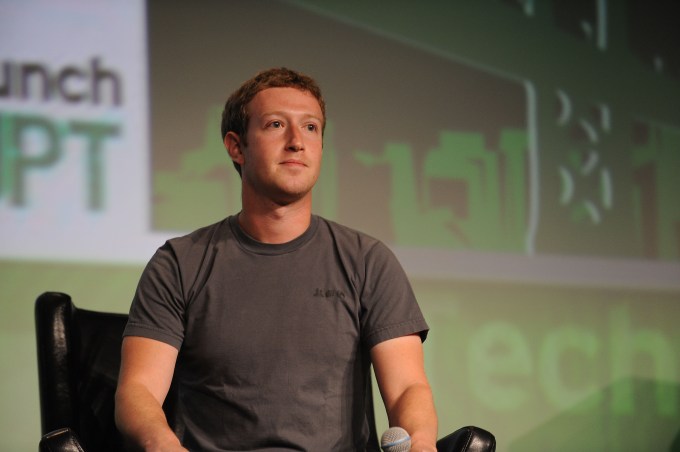

It’s becoming common to say that Mark Zuckerberg is coming under fire, but the Facebook CEO is again being questioned, this time over a recent claim that Facebook’s internal monitoring system is able to thwart attempts to use its services to incite hatred.

Speaking to Vox, Zuckerberg used the example of Myanmar, where he claimed Facebook had successfully rooted out and prevented hate speech through a system that scans chats inside Messenger. In this case, Messenger had been used to send messages to Buddhists and Muslims with the aim of creating conflict on September 11 last year.

Zuckerberg told Vox:

The Myanmar issues have, I think, gotten a lot of focus inside the company. I remember, one Saturday morning, I got a phone call and we detected that people were trying to spread sensational messages through — it was Facebook Messenger in this case — to each side of the conflict, basically telling the Muslims, “Hey, there’s about to be an uprising of the Buddhists, so make sure that you are armed and go to this place.” And then the same thing on the other side.

So that’s the kind of thing where I think it is clear that people were trying to use our tools in order to incite real harm. Now, in that case, our systems detect that that’s going on. We stop those messages from going through. But this is certainly something that we’re paying a lot of attention to.

That claim has been rejected in a letter signed by six organizations in Myanmar, including tech accelerator firm Phandeeyar. Far from a success, the group said the incident shows why Facebook is not equipped to respond to hate speech in international markets since it relied entirely on information from the ground, where Facebook does not have an office, in order to learn of the issue.

The group — which includes hate speech monitor Myanmar ICT for Development Organization and the Center for Social Integrity — explained that some four days elapsed between the sending of the first message and Facebook responding with a view to taking action.

In your interview, you refer to your detection ‘systems’. We believe your system, in this case, was us – and we were far from systematic. We identified the messages and escalated them to your team via email on Saturday the 9th September, Myanmar time. By then, the messages had already been circulating widely for three days.

The Messenger platform (at least in Myanmar) does not provide a reporting function, which would have enabled concerned individuals to flag the messages to you. Though these dangerous messages were deliberately pushed to large numbers of people – many people who received them say they did not personally know the sender – your team did not seem to have picked up on the pattern. For all of your data, it would seem that it was our personal connection with senior members of your team which led to the issue being dealt with.

Myanmar has only recently embraced the internet in recent times, thanks to the slashing of the cost of a SIM card — which was once as much as $300 — but already most people in the country are online. Since its internet revolution has taken place over the last five years, the level of Facebook adoption per person is one of the highest in the world.

“Out of a 50 million population, there are nearly 30 million active users on Facebook every month,” Phandeeyar CEO Jes Petersen told TechCrunch. “There’s this notion to many people that Facebook is the internet.”

Young men browse their Facebook wall on their smartphones as they sit in a street in Yangon on August 20, 2015. Facebook remains the dominant social network for US Internet users, while Twitter has failed to keep apace with rivals like Instagram and Pinterest, a study showed. AFP PHOTO / Nicolas ASFOURI (Photo credit should read NICOLAS ASFOURI/AFP/Getty Images)

Facebook optimistically set out to connect the world, and particularly facilitate communication between governments and people, so that statistic may appear at face value to fit with its goal of connecting the world, but the platform has been abused in Myanmar.

Chiefly that has centered around stoking tension between the Muslim and Buddhist populations in the country.

The situation in the country is so severe that an estimated 700,000 Rohingya refugees are thought to have fled to neighboring Bangladesh following a Myanmar government crackdown that began in August. U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has labeled the actions as ethnic cleansing, as has the UN.

Tensions inflamed, Facebook has been a primary outlet for racial hatred from high-profile individuals inside Myanmar. One of them, monk Ashin Wirathu who is barred from public speaking due to past history, moved online to Facebook where he quickly found an audience. Though he had his Facebook account shuttered, he has vowed to open new ones in order to continue to amplifly his voice via the social network.

Beyond visible figures, the platform has been ripe for anti-Muslim and anti-Rohinga memes and false new stories to go viral. UN investigators last month said Facebook has played a key role spreading hate.

Petersen said that Phandeeyar — which helped Facebook draft its local language community standards page — and others have held regular information meetings with the social network on the occasions that it has visited Myanmar. But the fact that it does not have an office in the country nor local speakers on its permanent staff has meant that little to nothing has been done.

Likewise, there is no organizational structure to handle the challenging situation in Myanmar, with many of its policy team based in Australia, and Facebook itself is not customized to solicit feedback from users in the country.

“If you are serious about making Facebook better, we urge you to invest more into moderation — particularly in countries, such as Myanmar, where Facebook has rapidly come to play a dominant role in how information is accessed and communicated,” the group wrote.

“We urge you to be more intent and proactive in engaging local groups, such as ours, who are invested in finding solutions, and — perhaps most importantly — we urge you to be more transparent about your processes, progress and the performance of your interventions, so as to enable us to work more effectively together,” they added in the letter.

Facebook has offices covering five of Southeast Asia’s largest countries — Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines — and its approach to expansion has seemed to focus on advertising sales opportunities, with most staff in the region being sales or account management personnel. Using that framing, Myanmar — with a nascent online advertising space — isn’t likely to qualify for an office, but Phandeyaar’s Petersen believes there’s a strong alternative case.

“Myanmar could be a really good test market for how you fix these problems,” he said in an interview. “The issues are not exclusive to Myanmar, but Facebook is so dominant and there are serious issues in the country — here is an opportunity to test ways to mitigate hate speech and fake news.”

Indeed, Zuckerberg has been praised for pushing to make Facebook less addictive, even at the expense of reduced advertising revenue. By the same token, Facebook could sacrifice profit and invest in opening more offices worldwide to help live up to the responsibility of being the de facto internet in many countries. Hiring local people to work hand-in-hand with communities would be a huge step forward to addressing these issues.

With over $4 billion in profit per quarter, it’s hard to argue that Facebook can’t justify the cost of a couple of dozen people in countries where it has acknowledged that there are local issues. Like the newsfeed changes, there is probably a financially-motivated argument that a safer Facebook is better for business, but the humanitarian responsibility alone should be enough to justify the costs.

In a statement, Facebook apologized that Zuckerberg had not acknowledged the role of the local groups in reporting the messages.

“We took their reports very seriously and immediately investigated ways to help prevent the spread of this content. We should have been faster and are working hard to improve our technology and tools to detect and prevent abusive, hateful or false content,” a spokesperson said.

The company said it is rolling a feature to allow Messenger users to report abusive content inside the app. It said also that it has added more Burmese language reviewers to handle content across its services.

“There is more we need to do and we will continue to work with civil society groups in Myanmar and around the world to do better,” the spokesperson added.

The company didn’t respond when we asked if there are plans to open an office in Myanmar.

SAN FRANCISCO, CA – SEPTEMBER 11: Facebook Founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg speaks during the TechCrunch Conference at SF Design Center on September 11, 2012 in San Francisco, California. (Photo by C Flanigan/WireImage)

Zuckerberg’s interview with Vox itself was one of the first steps of a media campaign that the Facebook supremo has embarked on in response to a wave of criticism and controversy that the company has weathered over the way it handles user data.

Facebook was heavily criticised last year for allowing Russian parties to disrupt the 2016 U.S. election using its platform, but the drama has intensified in recent weeks.

The company’s data privacy policy came under fire after it emerged that a developer named Dr. Aleksandr Kogan used the platform to administer a personality test app that collected data about participants and their friends. That data was then passed to Cambridge Analytica where it may have been leveraged to optimize political campaigns including that of 2016 presidential candidate Donald Trump and the Brexit vote, allegations which the company itself vehemently denies. Regardless of how the data was employed to political ends, that lax data sharing was enough to ignite a firestorm around Facebook’s privacy practices.

Zuckerberg himself fronted a rare call with reporters this week in which he answered questions on a range of topics, including whether he should resign as Facebook CEO. (He said he won’t.)

Most recently, Facebook admitted that as many as 87 million people on the service may have been impacted by Cambridge Analytica’s activities. That’s some way above its initial estimate of 50 million. Zuckerberg is scheduled to appear in front of Congress to discuss the affair, and likely a whole lot more, on April 11.

Following the Cambridge Analytica revelations, the company’s stock dropped precipitously, wiping more than $60 billion off its market capitalization from its prior period of stable growth.

Added to this data controversy, Facebook has been found to have deleted messages that Zuckerberg and other senior executives sent to some users, as TechCrunch’s Josh Constine reported this week. That’s despite the fact that Facebook and its Messenger product do not allow ordinary users to delete sent messages from a recipient’s inbox.

Read Full Article

No comments:

Post a Comment